How CRB listing can be beneficial to borrowers

For many people, getting listed on Credit Reference Bureaus is distressing.

For many people, getting listed on Credit Reference Bureaus is distressing. Besides hurting their chances of getting credit in future, it dents reputations, making them look like terrible people who do not pay back what they borrow.

No wonder the excitement generated on social media by suspension of CRB listing as an emergency mitigation measure against effects of COVID-19.

However, experts insist that a listing in itself is not bad. Based on the credit scoring, it could even be beneficial to prospective borrowers.

“The real purpose of bureaus is not to deter people from borrowing. It is to build a credit profile from loans taken, from who and repayment patterns,” says the Managing Director of Metropol Corporation, Sam Omukoko, who adds that a good credit score can be used as a basis for negotiating favourable interest rates.

According to the Metropol Corporation MD, with the removal of caps, lenders’ rates should reflect risk profiles of borrowers. Unfortunately, information asymmetry prevails where lenders have more information than borrowers.

The CEO of Creditinfo, Kamau Kunyiha, blames banks for the perception that CRB listing has attracted amongst borrowers.

“The problem has been the way banks have used the information. Banks did not use it to differentiate between good and bad, CRB information was only used for punitive purposes. If one’s credit history was not good, then they simply lost access to loans. A reward system has never been established for good borrowers,” says Mr Kunyiha.

Mr Omukoko concurs that CRB information empowers borrowers. “Many prospective borrowers do not know that with the score, they do not need to take any rate that is offered to them. This gives them a choice of where to borrow from. With the score, requirements such as having held an account for some time before borrowing, have become obsolete”.

In fact, the inspiration behind creation of CRBs was to enhance access to credit by borrowers, previously hampered by lack of collateral that banks insisted on. Neither could lenders give credit against savings. This perception of elevated credit risk led to high interest rates, and defaults, leading to collapse of some banks.

“The defaulters were possibly the same clique hopping from one bank to another but could not be discovered because there was no information sharing mechanism from which they could be identified. This led to the creation of a Credit Information Sharing system, managed by CRBs as independent third-parties,” Mr Omukoko recalls.

Initially, banks were only required to share lists of defaulters. This was before regulations were amended in 2015 paving way for information on good borrowers to be submitted. Banks are now required to share this information by the tenth of the following month.

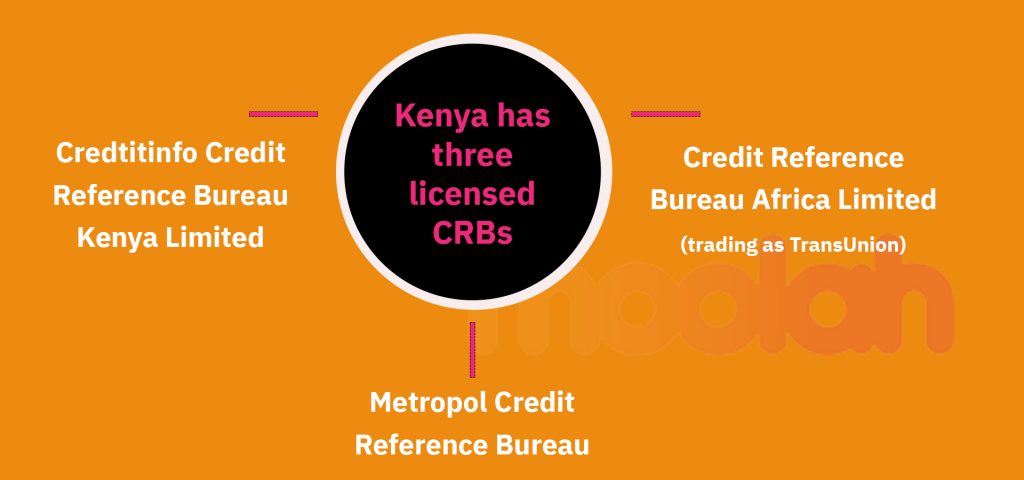

At the moment, Kenya has three licensed CRBs – Credit Reference Bureau Africa Limited (trading as TransUnion), Metropol Credit Reference Bureau Limited and Credtitinfo Credit Reference Bureau Kenya Limited. These firms collect and share information from approved credit information providers, namely, Savings and Credit Cooperatives (SACCOs), banks, and microfinance institutions. The mechanism is regulated by the Central Bank of Kenya, which approves the information providers.

Amongst them, Mr Kunyiha says, CRBs currently hold credit information of about 11 million people, complete with their borrowing trends.

Each borrower is assigned a credit score, ranging from 200 to 900, based on their borrowing behavior. The higher the score, the better the credit profile.

Mr Omukoko credits CRBs for aiding emergence of digital lenders, who did not have access to reliable information to facilitate automated lending decisions. Ironically, these digital lenders were recently axed from the list of approved credit information providers after running afoul with the regulator for wrongfully listing borrowers and being slow to make amends when questions are raised.

“Our intention is to bring all lenders into the mechanism. At the moment we have over 2,000 SACCOs, 400, microfinance institutions and 300 goods suppliers sharing credit information. We are working to rope in utility providers, namely electricity and water. The goal is to close in on having a single point of truth on anyone seeking to access credit in the market. This will aid a more accurate calculation of risk profiles of prospective borrowers,” he adds.

The challenge with utility providers, however, is the integrity of their data and even protocols for determining what constitutes a default.

The law entitles borrowers to a free report every year. Mr Omukoko says that borrowers have a recourse even when negatively listed for default arising from factors beyond their control. In such times, credit scores come in handy.

“One just needs to engage the lender on their reasons for default and negotiate for a review of the terms, perhaps by, based on the credit score, extending the repayment period, so as to reduce the instalments.